On Christmas Day, 1956, the police of the town of Herisau in eastern Switzerland were called out: children had stumbled upon the body of a man, frozen to death, in a snowy field. Arriving at the scene, the police took photographs and had the body removed.

The dead man was easily identified: Robert Walser, aged seventy-eight, missing from a local mental hospital. In his earlier years Walser had won something of a reputation, in Switzerland and even in Germany, as a writer. Some of his books were still in print; there had even been a biography of him published. During a quarter of a century in mental institutions, however, his own writing had dried up. Long country walks—like the one on which he had died—had been his main recreation.

The police photographs showed an old man in overcoat and boots lying sprawled in the snow, his eyes open, his jaw slack. These photographs have been widely (and shamelessly) reproduced in the critical literature on Walser that has burgeoned since the 1960s.1 Walser’s so-called madness, his lonely death, and the posthumously discovered cache of his secret writings were the pillars on which a legend of Walser as a scandalously neglected genius was erected. Even the sudden interest in Walser became part of the scandal. “I ask myself,” wrote the novelist Elias Canetti in 1973, “whether, among those who build their leisurely, secure, dead regular academic life on that of a writer who had lived in misery and despair, there is

one who is ashamed of himself.”

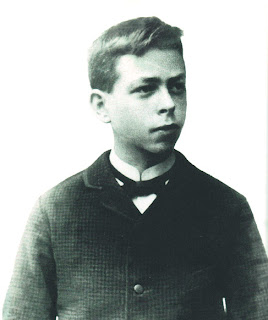

Robert Walser was born in 1878 in the canton of Bern, the seventh of eight children. His father, trained as a bookbinder, ran a store selling stationery and notions. At the age of fourteen Robert was taken out of school and apprenticed to a bank, where he performed his clerical functions in exemplary fashion. But, possessed by dreams of becoming an actor, he ran off to Stuttgart. His one and only audition proved a humiliating failure: he was dismissed as wooden and expressionless. Abandoning the stage, Walser decided to become—”God willing”—a poet. Drifting from job to job, he wrote poems, prose sketches, and little verse plays (“dramolets”), not without success. Soon he had been taken up by Insel Verlag, publisher of Rilke and Hofmannsthal, who put out his first book.

In 1905, intent on advancing his career, he followed his elder brother, a successful book illustrator and stage designer, to Berlin. There he enrolled in a training school for servants and worked briefly as a butler in a country house (he wore livery and answered to the name “Monsieur Robert”). Before long, however, he found he could support himself on the proceeds of his writing. He contributed to prestigious literary magazines, was accepted in serious artistic circles. But he was never at ease in the role of metropolitan intellectual; after a few drinks he tended to become rude and aggressively provincial. Gradually he retreated from society to a solitary, frugal life in bedsitters. In these surroundings he wrote four novels, of which three have survived:

The Tanner Children (1906),

The Factotum (1908), and

Jakob von Gunten (1909). All draw for their material on his own life experience; but in the case of

Jakob von Gunten—the best known of these early novels, and deservedly so—that experience is wondrously transmuted.

“One learns very little here,” observes young Jakob von Gunten after his first day at the Benjamenta Institute, where he has enrolled himself as a student. The teachers lie around like dead men. There is only one textbook, What is the Aim of Benjamenta’s Boys’ School?, and only one lesson, “How Should a Boy Behave?” All the teaching is done by Fräulein Lisa Benjamenta, sister of the principal. Herr Benjamenta himself sits in his office and counts his money, like an ogre in a fairy tale. In fact, the school is a bit of a swindle.

Nevertheless, having run away to the big city (unnamed, but clearly Berlin) from what he calls “a very, very small metropolis,” Jakob has no intention of giving up. He does not mind wearing the Benjamenta uniform; he gets on with his fellow students; and besides, riding the elevators downtown gives him a thrill, makes him feel thoroughly a child of his times.

Jakob von Gunten purports to be the diary Jakob keeps during his stay at the Institute. It consists mainly of his reflections on the education he receives there—an education in humility—and on the strange brother and sister who offer it. The humility taught by the Benjamentas is not of the religious variety. Their graduates aspire to be serving men or butlers, not saints. But Jakob is a special case, a pupil for whom the lessons in humility have a deep personal resonance. “How fortunate I am,” he writes, “not to be able to see in myself anything worth respecting and watching! To be small and to stay small.”

The Benjamentas are a mysterious and, at first sight, forbidding pair. Jakob sets himself the task of penetrating their mystery. He treats them not with respect but with the cheeky self-assurance of a child who is used to having any mischief on his part excused as cute, mixing effrontery with patently insincere self-abasement, giggling at his own insincerity, confident that candor will disarm all criticism, but not really caring if it does not. The word he would like to apply to himself, that he would like the world to apply to him, is

impish. An imp is a mischievous sprite; an imp is also a lesser devil.

Soon Jakob has begun to gain ascendancy over the Benjamentas. Fräulein Benjamenta hints that she is fond of him; he pretends not to understand. She reveals that what she feels is perhaps more than fondness, is perhaps love; Jakob replies with a long, evasive speech full of respectful sentiments. Thwarted, Fräulein Benjamenta pines away and dies.

Herr Benjamenta, initially hostile to Jakob, is maneuvered to the point of pleading with the boy to be his friend, to abandon his plans and come wandering the world with him. Primly, Jakob refuses: “But how shall I eat, Principal?… It’s your duty to find me a decent job. All I want is a job.” Yet on the last page of his diary he announces he is changing his mind: he will throw away his pen and go off into the wilderness with Herr Benjamenta (to which one can only respond: God save Herr Benjamenta!).

As a literary character, Jakob von Gunten is without precedent. In the pleasure he takes in picking away at himself he has something of Dostoevsky’s Underground Man and, behind him, of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau of the Confessions. But—as Walser’s first French translator, Marthe Robert, pointed out—there is in Jakob, too, something of the hero of the traditional German folk tale, of the lad who braves the castle of the giant and triumphs against all odds. Franz Kafka, early in his career, admired Walser’s work (Max Brod records with what delight Kafka would read Walser’s humorous sketches aloud). Barnabas and Jeremias, Surveyor K.’s demonically obstructive “assistants” in The Castle, have Jakob as their prototype.

In Kafka one also catches echoes of Walser’s prose, with its lucid syntactic layout, its casual juxtapositions of the elevated with the banal, and its eerily convincing logic of paradox. Here is Jakob in reflective mood:

We wear uniforms. Now, the wearing of uniforms simultaneously humiliates and exalts us. We look like unfree people, and that is possibly a disgrace, but we also look nice in our uniforms, and that sets us apart from the deep disgrace of those people who walk around in their very own clothes but in torn and dirty ones. To me, for instance, wearing a uniform is very pleasant because I never did know, before, what clothes to put on. But in this, too, I am a mystery to myself for the time being.

What is the mystery of Jakob? Walter Benjamin wrote a piece on Walser that is all the more striking for being based on a very incomplete acquaintance with his writings. Walser’s people, suggested Benjamin, are like fairy-tale characters once the tale has come to an end, characters who now have to live in the real world. There is something “laceratingly, inhumanly, and unfailingly superficial” about them, as if, having been rescued from madness (or from a spell), they must tread carefully for fear of falling back into it.

Jakob is such an odd being, and the air he breathes in the Benjamenta Institute is so rare, so near to the allegorical, that it is hard to think of him as representative of any element of society. Yet in Jakob’s cynicism about civilization and about values in general, his contempt for the life of the mind, his simplistic beliefs about how the world really works (it is run by big business to exploit the little man), his elevation of obedience to the highest of virtues, his readiness to bide his time, awaiting the call of destiny, his claim to be descended from noble, warlike ancestors (when the etymology he himself hints at for von Gunten—

von unten, “from below”—suggests otherwise), as well as his pleasure in the all-male ambience of the boarding school and his delight in malicious pranks—all of these features, taken together, point prophetically toward the petit-bourgeois type that, in times of greater social confusion, would find Hitler’s Brownshirts so attractive.

Walser was not an overtly political writer. Nevertheless, his emotional involvement with the class from which he came, the class of shopkeepers and clerks and schoolteachers, ran deep. Berlin offered him a clear chance to escape his social origins, to defect, as his brother had done, to the

déclassé cosmopolitan intelligentsia. He refused that offer, choosing instead to return to the embrace of provincial Switzerland. Yet he never lost sight of—indeed, was not allowed to lose sight of—the illiberal, conformist tendencies of his class, its intolerance of people like himself, dreamers and vagabonds.

In 1913 Walser left Berlin and returned to Switzerland “a ridiculed and unsuccessful author” (his own self-disparaging words). He took a room in a temperance hotel in the industrial town of Biel, near his sister, and for the next seven years earned a precarious living contributing feuilletons—literary sketches—to newspapers. For the rest he went on long country hikes and served out his obligations in the National Guard. In the collections of his poetry and short prose that continued to appear, he turned more and more to the Swiss social and natural landscape. He wrote two more novels. The manuscript of the first, Theodor, was lost by his publishers; the second, Tobold, was destroyed by Walser himself.

After the World War, the taste among the public for the kind of writing Walser had relied on for an income, writing easily dismissed as whimsical and belletristic, began to wane. He had lost touch with currents in wider German society; as for Switzerland, the reading public there was too small to support a corps of writers. Though he prided himself on his frugality, he had to close down what he called his “little prose-piece workshop.” He began to feel more and more oppressed by the censorious gaze of his neighbors, by the demand for respectability. He moved to Bern, to a position in the national archives, but within months had been dismissed for insubordination. He moved from lodgings to lodgings, drank heavily. He suffered from insomnia, heard imaginary voices, had nightmares and anxiety attacks. He attempted suicide, failing because, as he disarmingly admitted, “I couldn’t even make a proper noose.”

It was clear that he could no longer live alone. His family was, in the terminology of the times, tainted: his mother had been a chronic depressive; one brother had committed suicide; another had died in a mental hospital. It was suggested that his sister should take him in, but she was unwilling. So he allowed himself to be committed to the sanatorium in Waldau. “Markedly depressed and severely inhibited,” ran the initial medical report. “Responded evasively to questions about being sick of life.”

In later evaluations Walser’s doctors would disagree about what, if anything, was wrong with him, and would even urge him to try living outside again. However, the bedrock of institutional routine would appear to have become indispensable to him, and he chose to stay. In 1933 his family had him transferred to the asylum in Herisau, where he was entitled to welfare support. There he occupied his time with chores like gluing paper bags and sorting beans. He remained in full possession of his faculties; he continued to read newspapers and popular magazines; but, after 1932, he did not write. “I’m not here to write, I’m here to be mad,” he told a visitor. Besides, he said, the time for litterateurs was over. (Recently one of the Herisau staff claimed to have seen Walser at work writing. Even if this is true, no trace of such post-1932 writing has survived.)

Being a writer was difficult for Walser at the most elementary of levels. He did not use a typewriter, but wrote a clear, well-formed hand, on which he prided himself. The manuscripts that have survived—fair copies—are models of calligraphy. Handwriting was, however, one of the sites where psychic disturbance first manifested itself. At some time in his thirties (Walser is vague about the date) he began to suffer psychosomatic cramps of the right hand that he attributed to unconscious animosity toward the pen as a tool. He was able to overcome them only by abandoning the pen and switching to a pencil.

Use of a pencil was important enough for Walser to call it his “pencil system” or “pencil method.” What he does not mention is that when he moved to pencil-writing he radically changed his script. At his death he left behind some five hundred sheets of paper covered in a microscopic pencil script so difficult to read that his executor at first took them to be a diary in secret code. In fact Walser had kept no diary. Nor is the script a code: it is simply handwriting with so many idiosyncratic abbreviations that, even for editors familiar with it, unambiguous decipherment is not always possible. It is in these pencil drafts alone that Walser’s numerous late works, including his last novel,

The Robber (twenty-four sheets of microscript, 141 pages in print), have come down to us.

More interesting than the script itself is the question of what the “pencil method” made possible to Walser as a writer that the pen could no longer provide (he still used a pen for fair copies, as well as for correspondence). The answer seems to be that, like an artist with a stick of charcoal between his fingers, Walser needed to get a steady, rhythmic hand movement going before he could slip into a frame of mind in which reverie, composition, and the flow of the writing tool became much the same thing. In a piece entitled “Pencil Sketch” dating from 1926-1927, he mentions the “unique bliss” that the pencil method allowed him. “It calms me down and cheers me up,” he said elsewhere. Walser’s texts are driven neither by logic nor by narrative but by moods, fancies, and associations: in temperament he is less a thinker or storyteller than an essayist. The pencil and the self-invented stenographic script allowed the purposeful, uninterrupted, yet dreamy hand movement that had become indispensable to his creative mood.

The longest of Walser’s late works is The Robber, written in 1925-1926 but deciphered and published only in 1972. The story is light to the point of being insubstantial. It concerns the sentimental entanglements of a middle-aged man known simply as the Robber, a man who has no job but manages to exist on the fringes of polite society in Berne on the basis of a modest legacy.

Among the women the Robber diffidently pursues is a waitress named Edith; among the women who somewhat less diffidently pursue him are assorted landladies who want him either for their daughters or for themselves. The action culminates in a scene in which the Robber ascends the pulpit and, before a large assemblage, reproves Edith for preferring a mediocre rival to him. Incensed, Edith fires a revolver, wounding him slightly. There is a flurry of gleeful gossip. When the dust clears, the Robber is collaborating with a professional writer to tell his side of the story.

Why “the Robber” (

der Räuber) as a name for this timid gallant? The word hints, of course, at Walser’s first name. The cover of the University of Nebraska Press translation gives a further clue. It reproduces a watercolor by Karl Walser of his brother Robert, aged fifteen, dressed up as his favorite hero, Karl Moor in Schiller’s drama

The Robbers. The robber of Walser’s tale of modern times is, alas, no hero. A pilferer and plagiarist rather than a brigand, he steals at most the affections of girls and the formulas of popular fiction.

Behind Robber/Robert (whom I will henceforth call R) lurks a shadowy figure, the nominal author of the book, by whom R is treated now as a protégé, now as a rival, now as a mere puppet to be shifted around from situation to situation. He is critical of R (for handling his finances badly, for hanging around working-class girls, and generally for being a

Tagedieb, a day-thief or idler, rather than a good Swiss burgher), even though, he confesses, he has to keep his wits about him lest he confuse himself with R. In character he is much like R, mocking himself even as he plays out his social routines. Every now and again he has a flutter of anxiety about the book he is writing before our eyes—about its slow progress, the triviality of its content, the vacuity of his hero.

Fundamentally

The Robber is “about” nothing more than the adventure of its own writing. Its charm lies in its surprising twists and turns of direction, its delicately ironic handling of the formulas of amatory play, and its supple and inventive exploitation of the resources of German. Its author figure, flustered by the multiplicity of narrative strands he suddenly has to manage now that the pencil in his hand is moving, is reminiscent above all of Laurence Sterne, the gentler, later Sterne, without the leering and the double entendres.

The distancing effect allowed by an authorial self split off from an R self, and by a style in which sentiment is covered in a light veil of parody, allows Walser to write movingly, now and again, about his own (that is, R’s) defenselessness on the margins of Swiss society:

He was always…lone as a little lost lamb. People persecuted him to help him learn how to live. He gave such a vulnerable impression. He resembled the leaf that a little boy strikes down from its branch with a stick, because its singularity makes it conspicuous. In other words, he invited persecution.

As Walser remarked, with equal irony but

in propria persona, in a letter from the same period: “At times I feel eaten up, that is to say half or wholly consumed, by the love, concern, and interest of my so excellent countrymen.”

The Robber was not prepared for publication. In fact, in none of his many conversations with his friend and benefactor during his asylum years, Carl Seelig, did Walser so much as mention its existence. It draws on episodes from his life, barely disguised; yet one should be cautious about taking it as autobiographical. R embodies only one side of Walser. Though there are references to persecuting voices, and though R suffers from delusions of reference (he suspects hidden meaning, for example, in the way that men blow their noses in his presence), Walser’s own more melancholic, self-destructive side is kept firmly out of the picture.

In a major episode R visits a doctor and with great candor describes his sexual problems. He has never felt the urge to spend nights with women, he says, yet has “quite horrifying stockpiles of amorous potential,” so much so that “every time I go out on the street, I immediately start falling in love.” The only stratagem that brings him happiness is to think up stories about himself and his erotic object in which he is “the subordinate, obedient, sacrificing, scrutinized, and chaperoned [one].” Sometimes, in fact, he feels he is really a girl. Yet at the same time there is also a boy inside him, a naughty boy. The doctor’s response is eminently sage. You seem to know yourself very well, he says—don’t try to change.

In another remarkable passage Walser simply lets the pencil flow (lets the censor doze) as it leads him from the pleasures of “damselling”—living a feminine life imaginatively from the inside—to a richly erotic sharing of the experience of operatic lovers, to whom the bliss of pouring out one’s love in song and the bliss of love itself are one and the same.

Jakob von Gunten is translated in exemplary fashion by Christopher Middleton, a pioneering student of Walser and one of the great mediators of German literature to the English-speaking world of our time. In the case of The Robber, Susan Bernofsky rises splendidly to the challenge of late Walser, particularly his play with the compound formations to which German is so hospitable.

In an essay published in 1994, Bernofsky describes some of the problems that Walser presents to the translator.2 One of her illustrative passages is the following:

He sat in the aforementioned garden, entwined by lianas, embutterflied by melodies, and rapt in the rapscallity of his love for the fairest young aristocrat ever to spring down from the heavens of parental shelter into the public eye so as, with her charms, to give the heart of a Robber a fatal stab.

Bernofsky’s ingenuity in coining “embutterflied,” and her resourcefulness in postponing the punch to the final word, are admirable. But the sentence also illustrates one of the vexing problems of Walser’s microscript texts. The word translated here as “aristocrat,”

Herrentochter, is deciphered by another of Walser’s editors as

Saaltochter, Swiss German for “waitress.” (The woman in question, Edith, is certainly a waitress and no aristocrat.) Whose version are we to accept?

Now and again Bernofsky fails to rise to the challenge Walser sets. I am not sure that “scalawagging his way through [the] arcades” calls up the intended picture of a boy skipping school. One of the widows with whom R flirts is characterized as

ein Dummchen; and for two pages Walser rings the changes on

Dummheit in all its aspects. Bernofsky consistently uses “ninny” for

Dummchen and “ninnihood” for

Dummheit. “Ninny” has connotations of feeblemindedness, even of idiocy, absent from

Dumm-words, and is anyhow rarely used in contemporary English. Neither “ninny” nor any other single English word will translate

Dummchen, which has senses of “dummy” (someone who is dumb or stupid—the sense is stronger in American than in British English), “nitwit,” and even “airhead.”

Walser wrote in High German (

Hochdeutsch), the language that Swiss children learn in school. High German differs not only in a multitude of linguistic details but in its very temperament from the Swiss German that is the home language of three quarters of Swiss citizens. Writing in High German—which was, practically speaking, the only choice open to Walser—entailed, unavoidably, adopting a stance of a person of learning and of social refinement, a stance with which he was not comfortable. Though he had little time for a Swiss regional literature (

Heimatliteratur) dedicated to reproducing Helvetic folklore and celebrating dying folkways, Walser did, after his return to Switzerland, deliberately begin to introduce Swiss German into his writing, and generally to sound Swiss.

The coexistence of two versions of the same language in the same social space is a phenomenon without analogy in the metropolitan English-speaking world, and one that creates huge problems for the English translator. Bernofsky’s response to so-called dialect in Walser—comprising not just the odd word or phrase but a harder to define Swiss coloring to his language—is, candidly, to make no attempt to reproduce it: translating his Swiss-German moments by evoking some or other regional or social dialect of English will yield nothing, she says, but cultural falsification.

Both Middleton and Bernofsky write informative introductions to their translations, though Middleton’s is out of date on Walser scholarship. Neither chooses to provide explanatory notes. The absence of notes will be felt particularly in

The Robber, which is peppered with references to literature, including the obscurer reaches of Swiss literature.

The Robber is more or less contemporary in composition with Joyce’s Ulysses and with the later volumes of Proust’s Recherche. Had it been published in 1926 it might have affected the course of modern German literature, opening up and even legitimating as a subject the adventures of the writing (or dreaming) self and of the meandering line of ink (or pencil) that emerges under the writing hand. But that was not to be. Although a project to bring together Walser’s writings was initiated before his death, it was only after the first volumes of a more scholarly Collected Works began to appear in 1966, and after he had been noticed by readers in England and France, that he gained widespread attention in Germany.

Today Walser is judged largely on the basis of his novels, even though these form only a fifth of his output, and even though the novel proper was not his forte (the four novels he left behind really belong to the tradition of the novella). He is most at home in the mode of short fiction: pieces like “Kleist in Thun” (1913) and “Helbling’s Story” (1914) show him at his dazzling best. His own uneventful yet, in its way, harrowing life was his only true subject. All his prose pieces, he suggested in retrospect, might be read as chapters in “a long, plotless, realistic story,” a “cut up or disjoined book of the self [

Ich-Buch].”

Was Walser a great writer? If one is reluctant to call him great, said Canetti, that is only because nothing could be more alien to him than greatness. In a late poem Walser wrote:

I would wish it on no one to be me.

Only I am capable of bearing myself.

To know so much, to have seen so much, and

To say nothing, just about nothing.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/?page=3